Guest Essay: Trash Fashion!

Welcome to our latest guest takeover issue of The Dinamo Update. For these special mailings, I invite artists, writers, and other friends to think about design and fonts from a cultural or social perspective. And this time, Oslo-based Elise By Olsen writes on the graphic design of fashion—and why all the little pieces of ephemera around the industry are actually some of the worthiest things of collecting.

Elise By Olsen (b. 1999) is an editor, publisher, and the founding director International Library of Fashion Research, a cultural institution in Oslo, Norway. We’ve known her for years—and sent many of our fonts to her various publishing rooms. Elise created and edited the youth culture magazine Recens Paper (2013-2017) and the fashion commentary publication Wallet (2018-2021). In 2018 Gucci made a documentary about her work and in 2019 she guest-edited AnOther Magazine, where she currently writes one of my favorite monthly columns, “Paper View”. Over to Elise.

Trash FashioN!

Once, as a young aspiring fashionista, I went to Paris Fashion Week for the first time. I was 15 and accompanied by my mother. Before leaving I had printed out the official calendar from Paris Fashion Week’s glamorous website, and ticked off all the shows I wanted to attend with a red ballpoint pen. The most coveted show was, for me, back then, the Dior one. I believe it was the first collection by the then newly-appointed creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri, post-Raf Simons. I stepped up to the show’s designated venue, little me facing a colossal mirror-clad structure, by, I later learned, Bureau Betak.

The structure was placed in the cour carrée, the iconic courtyard of the Louvre. The facade reflected this historic site in the heart of the city. Gasp! I was amazed. Camera flashes from street style photographers hit the mirror wall panels and bounced back at bloggers, influencers, and over-the-top industry figures like a large reflector. Editors-in-chief and celebrities passed by the crowds and went inside. To see and be seen. Somewhere between a panic attack and Stendhal syndrome, I was already amazed by the show, even before entering myself, and even before the models and clothes.

My mother waited outside in the cour carrée with a cigarette in her hand as I snuck into the show—without invitation. I ran through the entrance, passed the uptight black-tie security guards, into long tubes that made a tunnel, which opened into a large spaceship-like hall, with stepped seating. The guests were already seated as security ran after me. Go, go, go! The lights dimmed just as I hid in the back row, camouflaged behind someone’s large, lavish hat. Lights dimmed. Guards stepped out. Models stepped in, onto the runway through a sequence of arched apertures, wearing grandiose habits. Showtime! As soon as it was over, the lights went back on. People left the premises in a hurry, likely to make it to the next one, or to get ahead of the taxi-lines that occupied the entire city during fashion week.

Top right: Elise’s stolen Dior invite, currently on display in the exhibition “Ephemeral Matters. Into the Fashion Archive” at the National Museum for Norway. Photo by Magnus Gulliksen.

Now, I love a good fashion show, but it’s what happened next that gave me an epiphany and that ultimately inspired my current infinity-project. Tightly dressed staff —interns?—immediately started vacuuming the floor. I stepped out of the nook I was hiding in and started picking up every invitation left behind on the front rows. Eureka! The invitations were precious. Grey stock, soft and gummy-like texture. The Dior logo embossed. Artistically presented, with handwritten names on them. Mademoiselle this-and-that. One man’s trash, et cetera!

I have no idea if people left the invitations behind deliberately, as an etiquette, a critical standpoint, or out of laziness, but they must have been expensive to make, I thought. And if I hadn’t picked them up they’d be thrown in the bin. These first rescued discards, show invites with strangers’ names on them, prompted my collection of fashion show remnants and remains that today makes up the collection of the International Library of Fashion Research in Oslo. What’s Nike without just doing it?

A library is both “symbol and reality of universal memory,” as author Umberto Eco said. I founded the International Library of Fashion Research in 2020, as a specialized library focused on fashion-related print materials. I wanted these historical documents, from books to magazines to show invitations (like my precious Dior invite) to press releases, things with high artistic production value as well as more rudimentary objects, to be available and accessible for everyone.

Given the increasing priority for everything to be digital, it felt crucial—perhaps more than ever—to preserve, document, and mediate fashion-focused printed matter, and to have it consolidated in one place. Thus, I wanted to create a meeting point for all kinds of researchers, professionals, and fashion enthusiasts worldwide to consult with this tactile material.

As digitization threatens the tradition of physical archiving, I wanted people to smell these objects, to touch them, to grapple with them with bare hands. To experience a slower, more thorough digest of information than what we are used to in this fast and accelerated digital climate. The archive as an antidote to our square eyes and ever shortening attention spans.

Now anyone can see and touch these show invites, which usually would have circulated within a very limited and gate kept milieu of VIP customers, buyers, and press. They were created by brands’ communications departments, hence the high production value. Now, again, we don’t know exactly why they’d leave them behind on the front row, but my theory would be that they were originally created for commercial ends with a promotional function, and therefore rarely given the intellectual study or consideration that they might deserve.

Sales materials are often dismissed and ignored. But fashion’s printed matter exists to promote or sell something, it creates allure and desire around products, and this is exactly what sets fashion apart from other industries. It’s also why I think we need to embrace such material: Commercial matter is the footprint of the industry, a powerful tool for understanding the industrial, historic, and symbolic evolution of fashion.

What I’ve come to learn is that many of the Maisons themselves, even, dispose of the invitations after they’ve been used! This became evident to me during the Covid-19 pandemic, when fashion’s accelerated apparatus was put on hold. Both material production (clothes, etc.) and immaterial production (campaigns, etc.) were put on standstill. In order to perpetuate the seasonal cycles (fashion never stops), the fashion house’s were forced to look into their own archives, to recycle or reuse material from the past.

A few months ago, when an executive from a top fashion house entered up the stairs of International Library of Fashion Research and wheezed, they confirmed my suspicion: that there was indeed a lack of documentation and archiving within the fashion apparatus. In order to make money and keep up with the fashion machine they tended to focus on the ‘next’ or the ‘new’. And in return, a lot of important—and historically valuable—ephemera, communications material, and advertising work were totally lost, disposed of. This made the urgency of my mission, from preserving fashion show scraps and other discards, all the more evident. I had to have the objects that the fashion houses themselves wouldn’t have. The burden of paper!

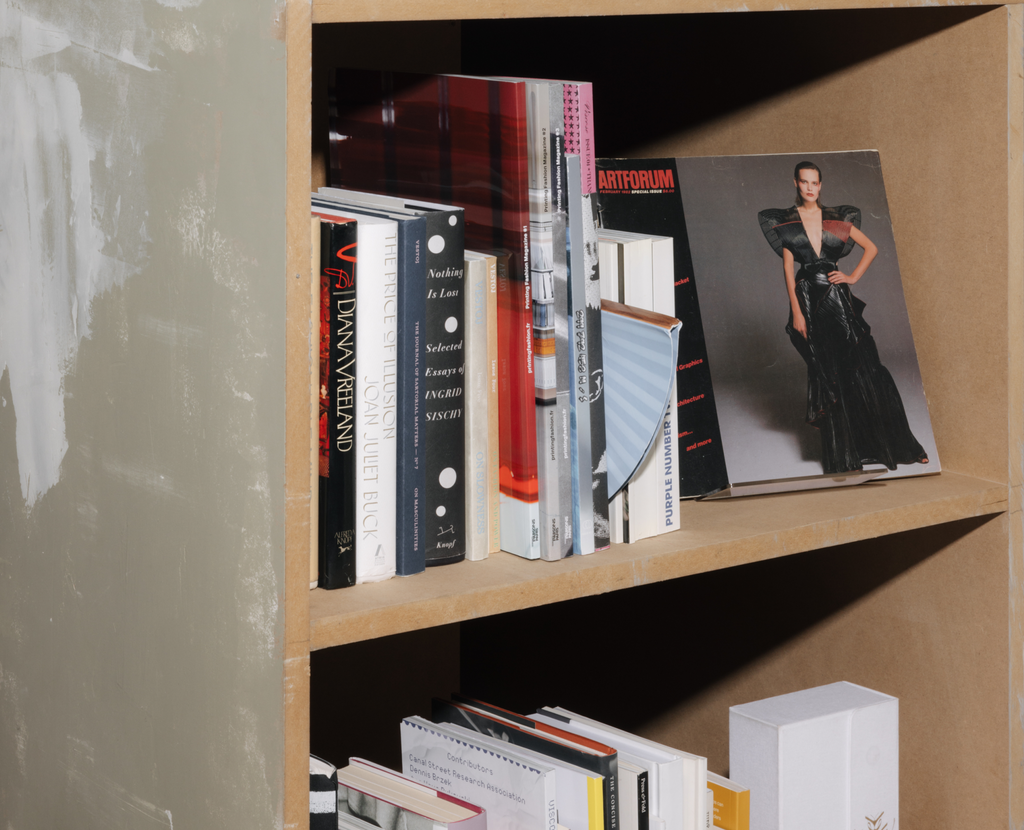

Let’s zoom out of the invitation-craze for a split second, and step into the library after closing hours. The aluminum shelves overflow with paper, reams and reams of them. I wanted to dust off, and bring these objects; fashion artifacts and cultural keepsakes, back to life, out of the trash. People across generations have all kinds of memories, anecdotes, and associations surrounding the objects that unfold while using and grappling with each piece. A library of oral stories! By activating the collection we ultimately prolong the objects’ lives. The archive is nothing without the bodies that touch them. We have magazines to take notes in and take notes from. We have books with dog ears. Promotional ephemera, rare objects, academic dissertations.

Graphically experimental magazine covers for The Face in the ’80s (the ’90s were devoted to photographic play) and Nest Magazine. Cult-covers of Italian Vogue, Purple Fashion, Acne Paper. Visionaries pushing formats and materials, pushing the boundaries between publication and artifact. We collect (or rather beg for) these objects deliberately, by reaching out to graphic designers and agencies who have been practicing in—and around— the field of fashion, such as M/M (Paris), Peter Saville, and Marc Ascoli, to fill holes in the collection. In the library, the work of graphic designers, photographers, stylists, copywriters, and even printing houses are represented. Love your-shelf!

Ephemera dresses up in different guises. Plays around with packaging, logos, and signatures. A logo in fashion typically changes as quickly as the industry moves. New insignias and identities rebranded. Often, in tandem with a new creative director, such as, exactly, Grazia after Simons, taking the helm of a fashion house. Creative directors want to solidify their stamp on the Maison, add their signature—signaling a new era. Celine without the accént, Saint Laurent without le Yves, a chunky all-caps Balenciaga. From sans to serif and back again. Let’s call it graphic evolutions!

And as creative director John Whelan claimed in a memorable Op-Ed in Business of Fashion back in 2019 called ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Serifised’, “every luxury brand’s logo looks the same.” And the piece continued, “fashion's branding clean slate is as much about erasing the past as it is about securing the future”. That’s all I could read before enabling a BoF membership. (And, speaking of plus features, just a train of thought: what’s the future of libraries? What happens if Google, in a few years, gets behind a paywall, will we then resort back to the libraries for information and data? Boom!)

Photograph by Magnus Gulliksen, courtesy International Library of Fashion Research.

Libraries and words go hand-in-hand, so how is text displayed in fashion? The interplay between fashion and text was interrogated in “Writing Clothes”, a recent exhibition at International Library of Fashion Research, curated by fashion scholars Laura Gardner & Jeppe Ugelvig. How is fashion constructed through text, language, and writing—in the past and present? Writing plays an important role in fashion, with the industry investing substantially in seasonally refreshing its visual messaging.

By collecting printed matter and fashion ephemera—from press releases to Vivienne Westwood’s manifestos to commercial monthly magazines such as Vanity Fair—the library doubles to collect the historical and contemporary practices of fashion writing within. From the work of professional fashion critics (such as Diana Vreeland, Helen Hessel), through to the appearance of fashion criticism in the spaces of art publishing (art is fashion’s cultural alibi—or ally?), and poetic capacities in work by fashion studios, artists and research projects. Text is an experimental tool in both fashion production and consumption—often mirroring dynamics found in industrial fashion.

Fashion writing often dresses up in different guises: as collection reviews, society columns, industry reports, or ethical investigations into businesses. Inversely, a lot of things dress up as fashion criticism, such as the promotion and marketing of fashion goods. From the poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s fashion magazine La Dernière Mode from 1974 and its texts that satirize the whole genre of fashion writing, to establishing wider terms for clothing and sartorial dictionaries (trousers have their own language!). Another notable contemporary example of fashion’s experimental language is the press releases of Comme des Garcons. The press release was presented orally: the brand’s CEO would step out on the runway before show start and give away two words, for example “flowers, yellow”. These show notes were left with the audience as a pendant for the insiders—press, buyers, VIPs—to interpret on their own.

Photograph by Magnus Gulliksen, courtesy International Library of Fashion Research.

What becomes obvious, when looking at all this ephemera, is how fashion language has changed over time. Press releases, and fashion language in general, have become more ‘artified’, overly explained or conceptualized, fluffy, taking shape as efficient, already-written journalistic pieces, for the brands to control their image, and for the journalists or critics to simply copy and press ‘publish’. Recently, it is the fashion critic that has jumped ship and turned copywriter for brands for a living. So on one hand, they are two separate tasks sewn together; one, shape up and perfect sentences for brand benefits, and on the other, to translate the social meaning of clothes through written words, to unravel all that perfection. Is the dichotomy—between criticism and commerce—ever totally clear in the realm of fashion? What’s the difference between fashion coverage and fashion criticism? For both designer and critic, fashion writing is a process of mystification, capable of revealing and concealing things that the image cannot.

From clothes in words to words on clothes. Garments may also function as ephemeral objects and communicative tools. The wearability becoming secondary. Such as Junya Watanabe’s poetry t-shirt to the merch of the anonymous troll-cum-critic Steve Oklyn’s, utilizing words and branding on clothes as a blatant critical gesture. Such work critically, and powerfully, interrogates the dynamic between word and garment. Clothes wearing words! And speaking of dressing up…. More than writing I like to switch up fonts to change the glam, the drama, the rhythm in my own fashion writing , in the process. It’s like changing outfits, becoming someone else, dress up and down, designer cosplay! Which font are you?

I am many things but also a young fashion enthusiast—from a generation that tends to get described as illiterate—who yet is still fascinated by the power of print, and the power of words. Stepping into the library, opening the gray shoebox-like archival cases with my now perfectly preserved Dior invites from 2015, makes me realize how much it all matters. Thinking about the appreciation and care that went into creating (and collecting) all these pieces of ephemera, in our sterilized AI present, our accelerated digital climate, is astonishing.

Books are data, too, and they must be read! I collect because I want to engage and encourage people to read and write fashion. This industry, fashion, that is flush with cash, has created all these things we consider seminal fashion printed matter today. Continuously collecting words of fashion—and the fashion of words—will create a living archive of fashion history. After all, we are only negatives in this geological age, and we need the time and space that a physical library experience allows for to potentially refine the state of 21st century cultural critique. I once placed my lousy Dior show invites on a higher conceptual plane—now they’re worth something after all!